Year in AI - 2020

As humans have been grappling with a pretty rough ride this year, how have machines been doing? Let’s find out in this small review!

Welcome, Gigantic Prolific Transformer III

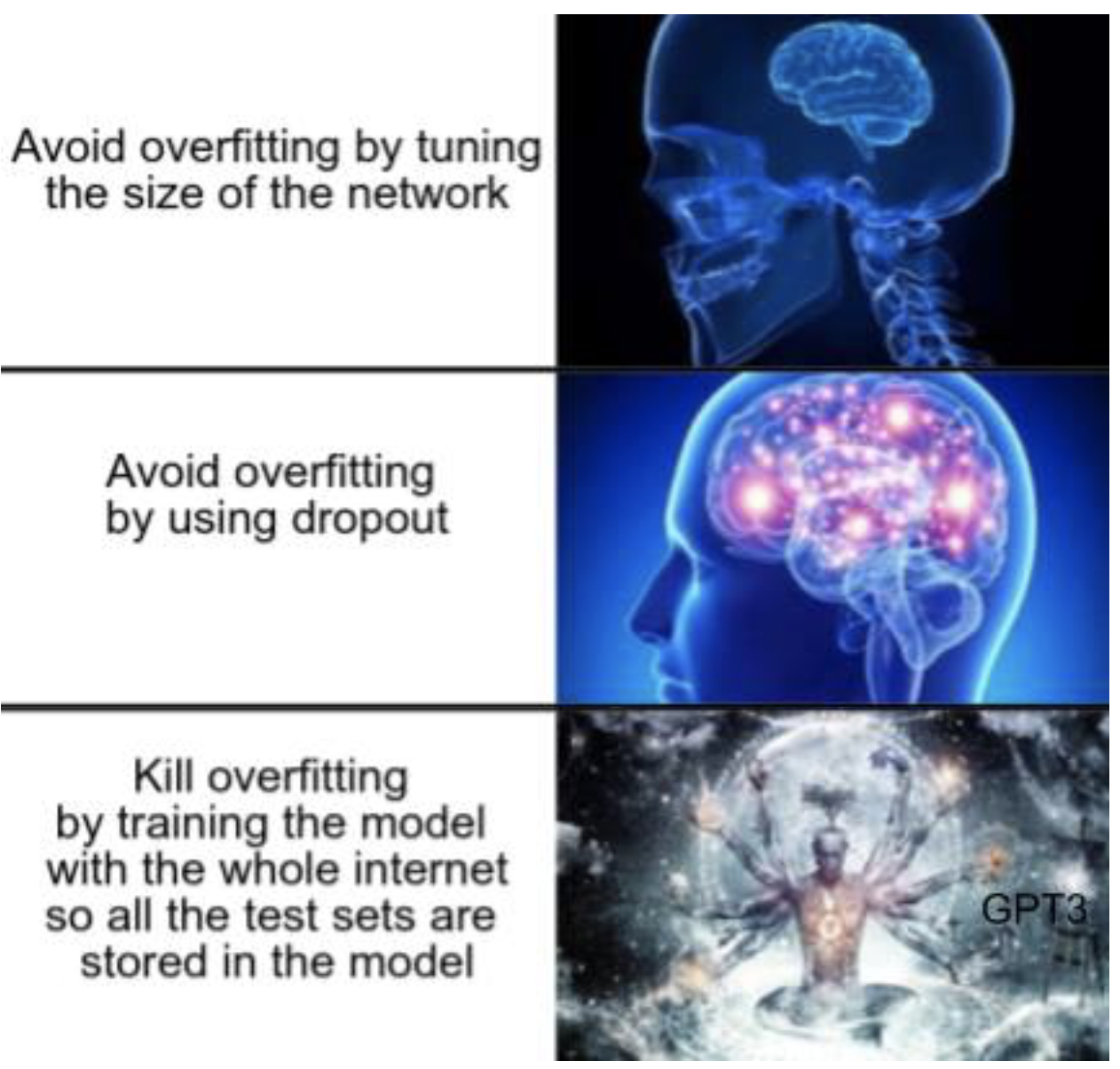

Let’s start with one of the most remarkable and buzz-generating AI releases of the year, I have named the infamous GPT-3, latest language model of a series developed by OpenAI. It is essentially a huge neural network with a Transformer architecture that is trained to accomplish any language task (question answering, text generation, chatbot…). Here when I say huge I really mean of mythological proportions: we are talking of a 175 billion-parameter model, which according to rumors was trained on something like 570 GB of text data, with a 5 to 10M$ budget for training alone! Although a Beta access for selected researchers was opened this summer, the model remains unavailable for the general public, and details about it have been published in the NeurIPS paper “Language Models are Few-Shot Learners” by Brown et al..

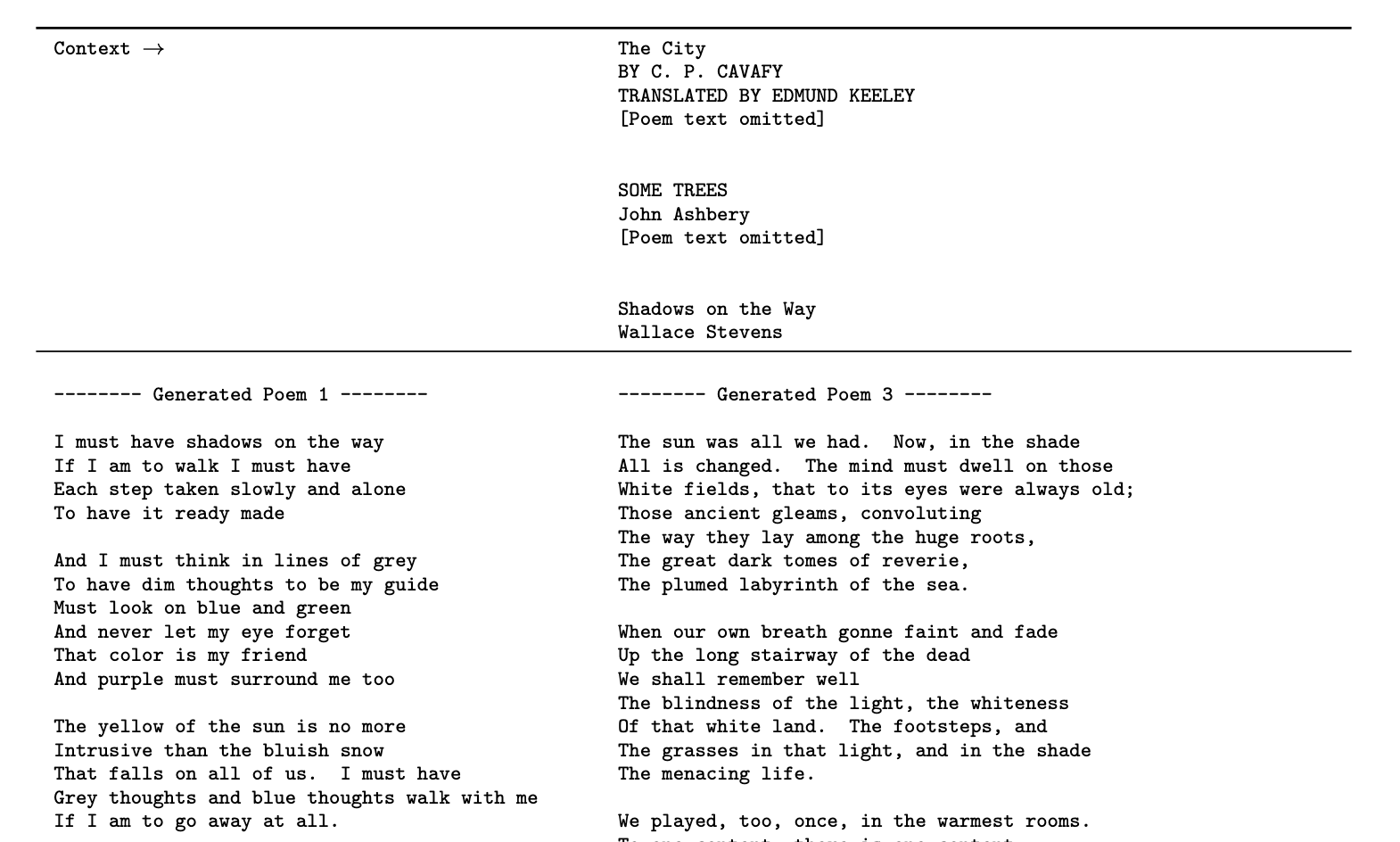

The way it works is that you provide GPT-3 with a prompt (aka context) that typically consists of a few examples (2 or 3 are enough) of the task you want to accomplish, or a simple question, or a text with questions about it, and GPT-3 will infer both what task it is supposed to do, and a text that fulfills the task. An example given in the paper would be to give GPT-3 2 example poems, and then a title and author name like illustrated below. GPT-3 will then understand that it is supposed to generate a poem titled Shadows on the Way in the style of Wallace Stevens and throw the best verses it can come up with (this is the few-shot learning mentioned in the paper’s title).

But what’s fascinating with language models are the endless possibilities they offer, and their capacity to amaze us in unpredictable, funny, or AI-will-take-over-the-world-scary ways. And GPT-3 is very, very good at this game. People have gotten it to generate startup ideas, share life advice from personalities, give creative writing lessons, share intimate worries about its own future, write a summary of experiments with itself and much more, the list could really go on forever. One particularity is it seems to abhor the sentence “I don’t know” and would rather improvise a plausible answer to anything (and it is quite an improvisational genius), unless you explicitly ask it for some honesty.

Despite being really good at spotting and imitating patterns, this model still seems to only be exploiting statistical regularities of an enormous language dataset, and doesn’t seem to actuallly understand the concepts it is talking about. It remains to be seen if those perks will always be around as long as we stick to purely statistical, system-1 AI, or if we just need to keep adding more parameters. In any case, I just hope we let the next language model choose itself a more inspiring pen name than GPT-4.

A machine learning machine learning

Meta-learning has been taking a lot of importance recently, with researchers designing algorithms that find new neural network architectures or that rediscover backpropagation. However, researchers always prompted their meta-learning algorithms to explore a restricted and already pre-designed set of learning algorithms (e.g. neural nets). In a paper presented at the ICML conference, Google Brain researchers Esteban Real, Chen Liang et al. exhibited AutoML-Zero, an algorithm that rediscovers machine learning algorithm only from basic computational bricks like vector operations, memory manipulation, and a few mathematical functions.

Their approach uses an evolutionary algorithm to rediscover such ML algorithms as linear regression or 2-layer perceptrons with backpropagation: a population of algorithms undergoes random mutations, and the best performing ones are selected at each generation. They remarkably end up exhibiting a really good performance on image recognition tasks and re-inventing “tricks of the trade” like gradient normalization or stochastic gradient descent.

So far all meta-learning research has focused on re-inventing human ideas. It will be really interesting to see if they can come up with ideas of novel algorithms some day.

OrigaML

Another mind-blowing AI news this year has been DeepMind’s announcement of their AlphaFold 2 model (no paper available yet) which really nailed the CASP protein-folding competition achieving a score higher than 80/100, more than a 2-fold improvement on pre-AlphaFold 1 models. Although I do not understand the full implications of this discovery, or even what this score exactly means, it is certainly uplifting to see AI tackle a very concrete problem in another science. Let’s hope for an AlphaCold model next to find a solution to global warming since humans don’t seem very good at it (although it would probably just end up designing new bat viruses if it’s smart enough. Meh, everything has its perks…).

Interesting links:

Mastering everything with Mu-Zero

DeepMind has decidedly had a productive year, also releasing a new paper in their reinforcement learning series (although this was on arXiv since 2019). The gist of it is that reinforcement algorithms so far are mostly divided into model-based algorithms and policy-gradient ones, at least until MuZero implemented indeas to reconcile those two approaches.

To understand this, here is a super quick recap’ on the reinforcement learning formalism: an agent evolves in an environment, which we can generally understand as something being in a certain state at each timestep \(s_t\) (the state can be modelled for example by the vector). The agent has to choose an action \(a_t\) at each timestep from its set of possible actions, and this will lead the environment to move to another state \(s_{t+1}\), and maybe give a reward (positive or negative) to the agent \(r_t\). The objective of the agent is to maximize the total reward during a trial \(\sum_{t=0}^T r_t\) (sometimes using discounted reward, but let’s not go into the details here).

The model-based algorithms relie on a model of the exact rules of the environment. The algorithm has to learn 2 things: how the environment transitions from one state to another (mathematically a mapping from a state and an action to the next state \((s_t, a_t) \to s_{t+1}\)), and which states lead to more reward (a mapping from states to expected final reward, aka the value function, \(s_t \to v_t = \sum_{\tau > t} r_\tau\)). Once the algorithm learns these mappings (which it does by exploring its environment), it can start exploitation, meaning choosing at each step the action that leads to the state with the highest value. Since the value function incorporates knowledge about future timesteps, the algorithm is naturally planning several steps ahead. Thanks to these planning capacities, these algorithms are very good for board games like chess and go, but they behave badly when the state-space cannot be described succintly like in complex video games.

On the other hand, policy-gradient algorithms just give up trying to build a model of their environment and try to focus on getting instincts, predicting which action to take next depending on environment variables. They just learn a state -> action mapping which maximizes some performance measure. This led to the famous actor-critic algorithms like A3C which holds one of the best performances on a set of 57 Atari games often used in RL research, or AlphaStar which famously reached superhuman capacities at the StarCraft game in 2019.

The interesting novelty of Mu-Zero is that it is able to combine the best of both worlds. For this, it relies on a hidden state representation of the environment (called \(s_t\) in the paper, I will call it here \(\hat{s}_t\) to emphasize that it is model-built), for which a dynamical model is learned, along with a policy and a value function. If we simplify it a little, the model essentially learns:

- a representation function mapping from past observation to a hidden state representation of the environment (mathematically \(\hat{s}_t = h_\theta(o_1, …, o_t)\) )

- a dynamics function which is a (hidden state, action) tuple to the next hidden state, and reward obtained (mathematically \((r_t, \hat{s}_{t+1}) = g_\theta(\hat{s}_t, a_t)\) )

- a prediction function which maps from a state to a policy (choice of action) and a current value (mathematically \((a_t, v_t) = f_\theta(\hat{s}_t)\))

The fact that the state representations are learned from observations of the environment enable the algorithm to learn in very complex environments, but the fact that this state representation still exists gives the possibility of planning ahead, which is an interesting compromise. There is a bit more to it, but if I continue I will be longer than the paper itself.

Lottery tickets everywhere!

Lottery tickets were a remarkable theoretical insight of 2019, published by Frankle and Carbin. Briefly, it is a story that started as researchers were looking for ways to prune very big networks after training in order to have more lightweight and faster networks whose performance could match that of the big one. The authors discovered that they could train a big network, prune it, reset the weights of the pruned network to their value before training, retrain, and at the end of this procedure obtain networks which have the same performance as that of the big one with as little as 5% of the initial number of parameters. This phenomenon is probably caused by the fact that by chance, the initial weights of this subnetwork were relevant to the task, so they dubbed their discovery the “lottery ticket hypothesis”, because the pruned subnetworks had won the “initialization lottery”.

This paper opened a whole new area of research, and led to even more surprising developments this year. New discoveries appeared at AAAI20, where Yulong Wang et al presented Pruning from Scratch, a paper showing that the first step of the lottery ticket procedure (pre-training the network) was not necessary, and that winning tickets could be directly found from the randomly initialized network. Authors claim that their pipeline is extremely fast, although I have not found a clear comparison between the pruning + training procedure and a normal training on the big network.

But the most surprising development came at the CVPR conference, where Vivek Ramanujan, Mitchell Wortsmann and others published What’s Hidden in a Randomly Weighted Neural Network ? showing that big networks actually contained subnetworks that were efficient in solving the task without any learning involved!! As a striking example, they claim that “Hidden in a randomly weighted Wide ResNet-50 we find a subnetwork (with random weights) that is smaller than, but matches the performance of a ResNet-34 trained on ImageNet” (to give you an idea, Resnet-50 contains 210M trainable parameters, and Resnet-34 21M, so by achieving a more than 10% reduction we can get a performing network without any training). They present an algorithm to find these miraculous subnetworks, which I have to admit bears a lot of resemblance to a gradient descent (it essentially involves updating scores for each neuron by a rule based on a gradient, and then selecting for each layer the k% of neurons having the highest score), although it is now entirely focused on pruning connexions. Again, it would be interesting to know how this procedure compares to training a network that achieves the same accuracy. However, even if we put aside all practical considerations, this remains an important theoretical milestone in our understanding of deep networks. It is an entirely new form of learning algorithm, which underlines the importance of random structures in learning, and is of course quite reminiscent of the ideas of “synaptic pruning” in the brain. It reminds me a lot of the “reverse learning” hypothesis formulated by Crick and Mitchison in 1983, according to which the brain learns by erasing unwanted memories during REM sleep. If pruning turns out to be enough, might it be the long-awaited learning algorithm of our brains?

But let’s not get carried away to far. A third impressive novelty 2020 has brought to this lottery ticket hypothesis is a flurry of theoretical bounds showing how big a network has to be in order to contain those magical winning subnetworks. They have culminated on the similar concurrent discoveries published at Neurips by Orseau et al. and Pensia et al., who both proved that one could find a good subnetwork of width \(d\) and depth \(l\) by pruning a big random of size \(\mathcal{O}(Poly(dl))\) (a polynomial of \(d\) and \(l\)), which is not that big!

Interesting links:

- A great informal review of lottery ticket-related papers

- A Tech Review article about the original Frankle and Carbin discovery

Best of AI dark magic tricks

Computer vision research always has a twist to amaze us, and here are some of my favourite releases of the year:

-

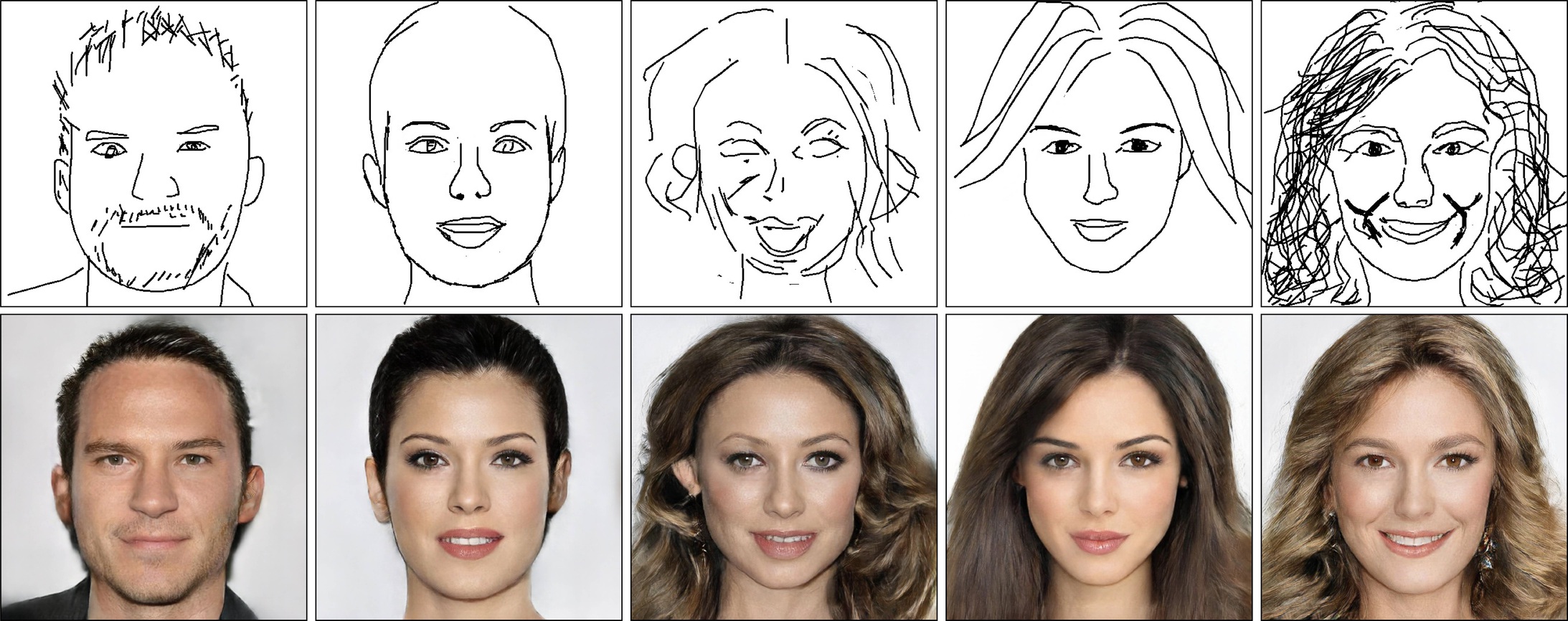

DeepFaceDrawing : Chen, Su et al. presented at Siggraph an interesting project that generates realistic pictures from very rough drawings. I haven’t looked at the details, but it essentially looks like a GAN conditioned on an input sketch, with the sketches and realistic images both sharing a common abstract feature space. Now I can’t wait for “xkcd : the movie” to be generated with this network! (Project page)

-

Neural Re-Rendering of Humans from a Single Image : Sarkar et al. from the Saarland MPI presented at ECCV what looks like a new DL-based motion capture technology : take a still image of Alice, and a live footage of Bob dancing the macarena, and the network shall combine it into a live footage of Alice dancing the macarena (keeping Alice’s clothes and silhouette, in contrast with previous deepfakes which only applied a new face onto the footage). This builds on a lot of complex modules (pose estimation, texture inference and adversarial rendering of images), and gives overall very convincing results for pose transfer. (Project page)

-

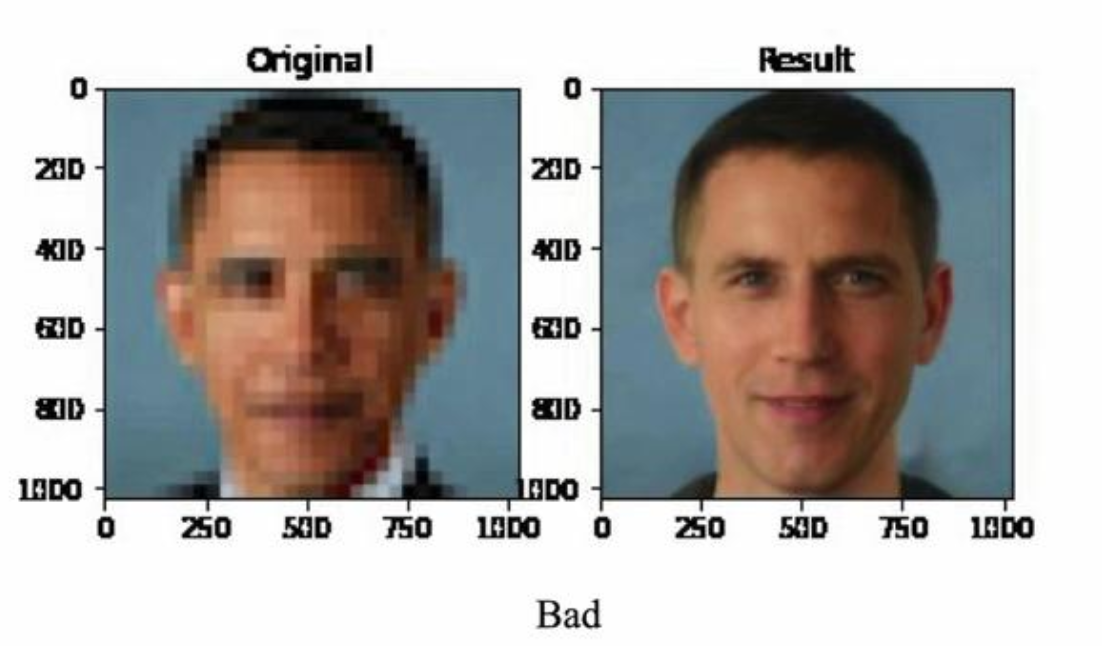

PULSE: Self-supervised Photo Upsampling via Latent Space Exploration of Generative Models: this grandiloquent name hides a very nice project presented at CVPR by Menon, Damian et al from Duke for generating hig-res images from low-res ones (and maybe finally give some credibility to those scenes where FBI agent zoom into sunglass reflections of the bad guy to see who he was talking to). As you can see from the image below, it really works with only a bunch of pixels as inputs, and just like DeepFaceDrawing can be understood as a conditional generative model with common latent space for blurry and high-res images. Charles Isbells has pointed to interesting biases of this network in his Neurips keynote, where a downsampled image of Obama would essentially generate an image of a white man with a tan. (Paper)

PULSE upscaling skills

This, children, is a bias

To my greatest regret I have to leave you here, while I am sure there are a lot of awesome stories I have missed. Feel free to reach me on twitter if you have any comments or want to point to a mistake!

Oh, and here are some robots taking over the dancefloor. Looks like I can learn from their leg twist!