A buzzword tour of 2021 in Neuro and AI

Between self-supervised approaches for transfer learning, contrastive losses and representational similarity analysis, these last few years were as rich in ideas as buzzing with confusing words. Here is a little dictionary to celebrate the end of 2021. If you have time for only one entry, check out the self-supervised learning one above all!

Disclaimer: don’t set your expectations too high, this is just a grad student’s attempt at making sense of his frenetic field.

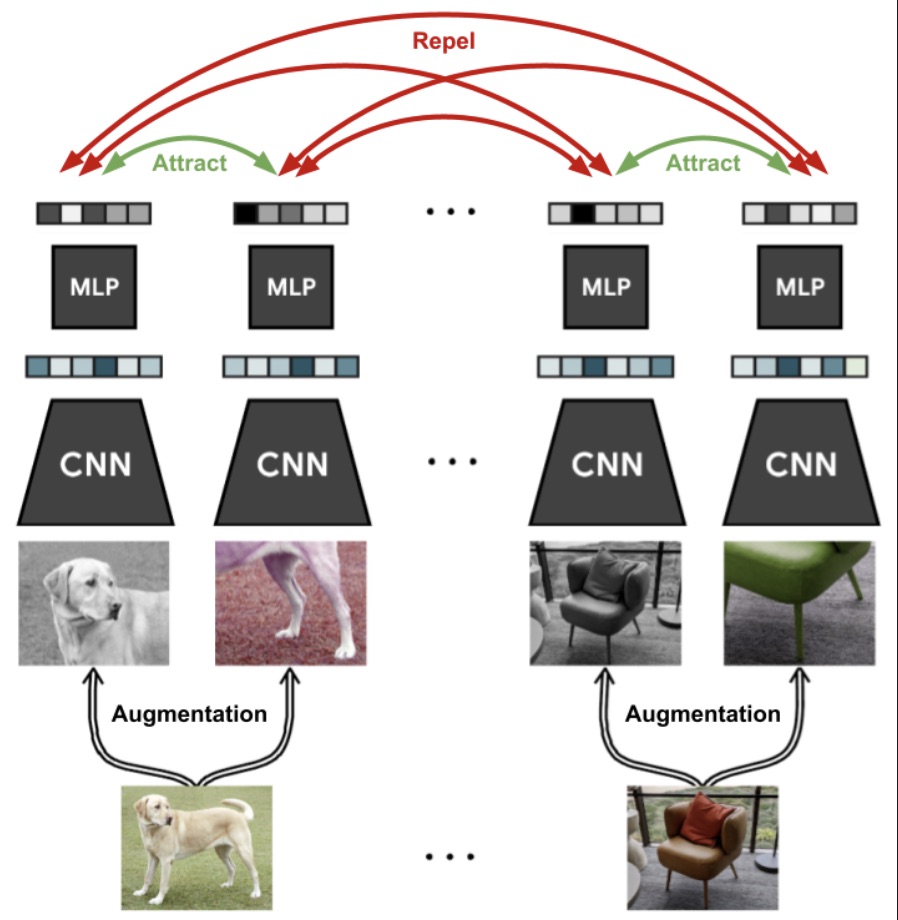

- Contrastive learning: One of the main paradigms for self-supervised learning (probably check that entry first). Here is a recipe for contrastive learning:

- take a dataset of items (sentences, or images for example)

- for each item, create a bunch of corrupted items (for example by masking words in sentences, or applying random crops and color filters to images)

- train a network to associate to each corrupted item the corresponding original one, by using a contrastive loss, a measure that should be low for matching items and high for non-matching ones.

An algorithm is then trained to match each corrupted item to the corresponding original one. An example where this is applied is for training modern language models, like GPT-3 (see last year’s post): they are usually trained on huge swaths of text where some words are masked, and a deep network has to find which are the most probable words for filling the gaps. This approach was actually used in most natural language processing innovations since 2013, and was notably critical in developing word embeddings like word2vec or Glove.

More recently, these methods have been used in computer vision, as was done by the SimCLR network published by Chen et al. which was the state of the art self-supervised vision algorithm in 2020. You can read more about it in the excellent post by Amit Chaudhary. Most recent developments include the SwAV method developed at Inria and Faceb… sorry Meta.

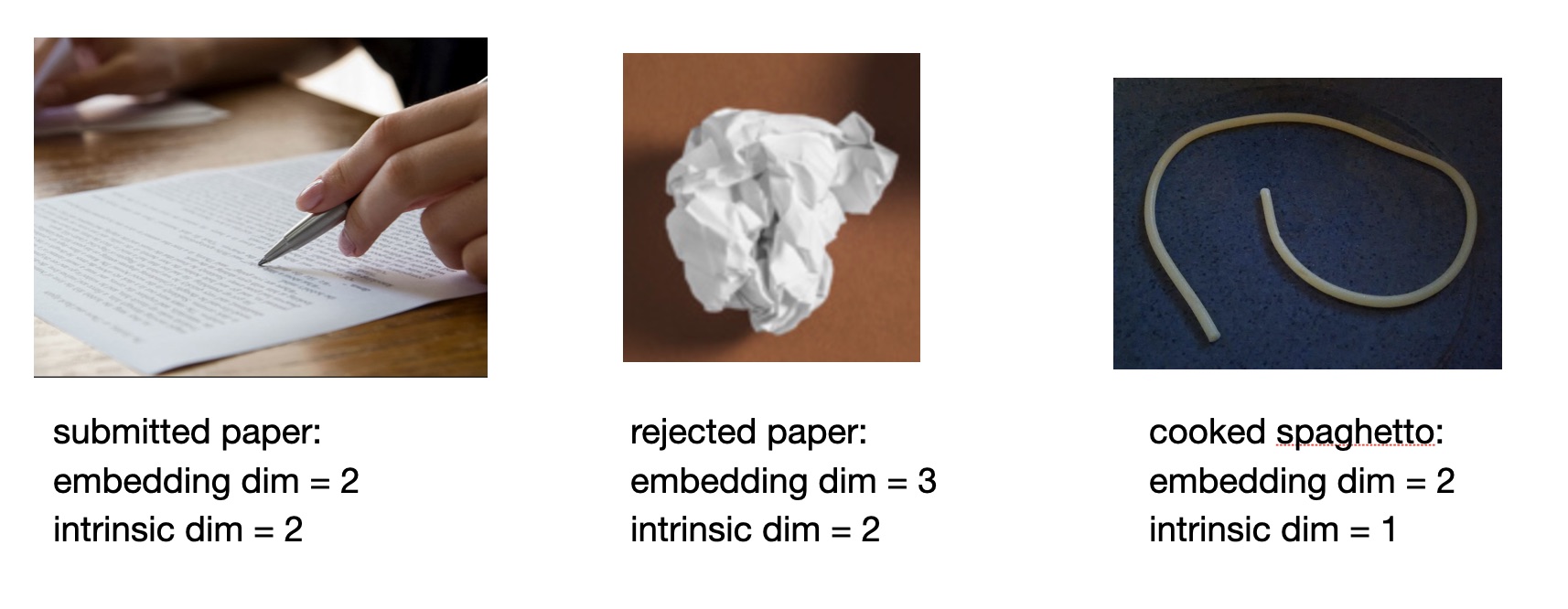

SimCLR's illustrated abstract - Dimensionality (intrinsic and embedding): In the last ten years the question of the dimensionality of representations, both in brains and artificial networks, has become increasingly important, notably because it hides a key compromise: as explained in the work of Stefano Fusi’s lab, while low dimensional representations make generalization easier, high dimensional ones make it easier to untangle non-linear representations and make them linearly separable. The tension between these concepts is more present than ever in works exploring the geometry of representations, sometimes showing contradictory finding between early and late layers of a same network (Recanatesi et al. 2021). Another notion that became increasingly important is often ignored difference between embedding dimensionality (as measured by PCA for example) and intrinsic dimensionality (the one measured by non-linear dimensionality reduction algorithms like t-SNE). To learn more about the subject one can read the review by Jazayeri and Ostojic or the thread by João Barbosa.

Embedding vs intrinsic dimensionality

- Dope: Because dopness in science is not over, and we might think every possible application of AI has been already done (including generating cake recipes), but we keep being surprised, here is a random collection of interesting tidbits:

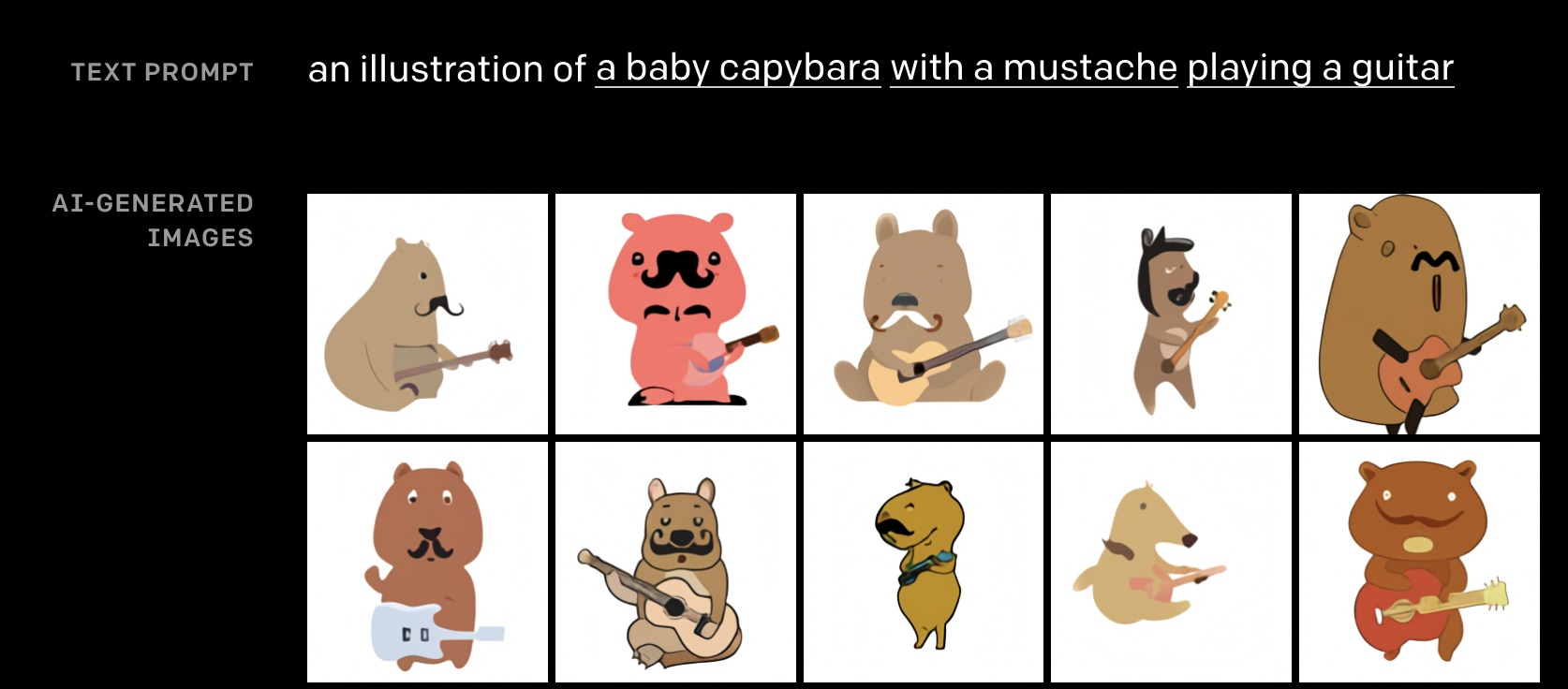

- OpenAI released an artificial painter which generates images based on written instructions, and goes by the name Dall-E (lol).

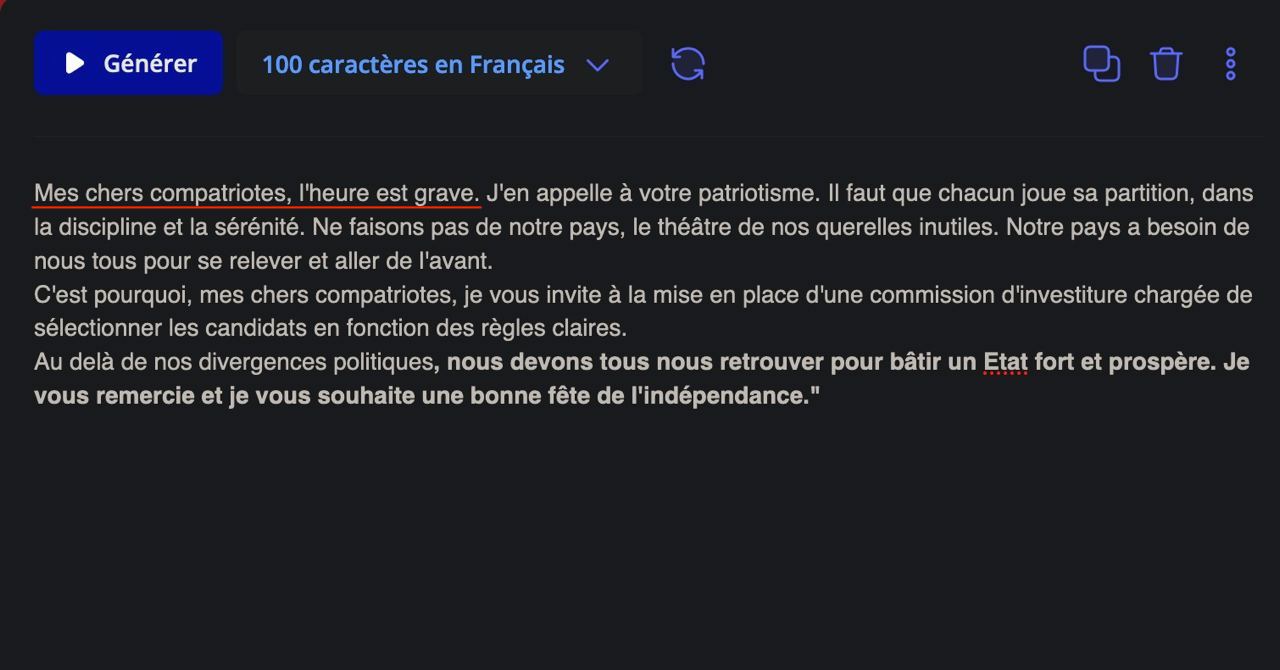

- A Swiss startup released a huge language model akin to GPT-3, mais en français, enfin ! Called Cedille it can be tested on their website for free, displays an amazing performance, and can write very good samples of what we in France call langue de bois (political speeches). Will the candidates for next election use it?

- Discovered it this year although they’ve shown good performance for a little more time, but I was stunned by the quality of musical compositions written by the artificial composer AIVA, developed by a Luxembourg-based company. (Minus points for the name though, I preferred the “Bachprop” algorithm).

- I should mention this somewhere, but while last year people were astonished by the performance of AlphaFold in uncovering the 3D structure of proteins from their sequences, this year everyone was happy at the double release of a paper by the AlphaFold team with its code, and the release of the concurrent, open-source, academically-led RoseTTA project in a (non-open) journal.

- Many other crazy and not-so-useful-but-quite-funny things like this Meta website for animating children drawings.

Example images generated by Dall-E from a text prompt

Inspiring speech generated by Cedille (prompt in red)

- Double descent: with lottery tickets this has been one of the most puzzling theoretical insights lately, shaking common beliefs about overfitting and generalization. In a 2019 PNAS paper, Mikhail Belkin et al. (see also Advani and Saxe) showed this intriguing phenomenon: train a model on a dataset of size $n$ and increase its number of parameters $p$ from very low values. Initially, the model will be underfitting the data and its loss will decrease, until when $p$ becomes too large it will start to overfit and the loss will increase again. So far, so good. Here is the catch: if you keep increasing $p$, after attaining a peak at $p=n$ where the model perfectly learns the whole data, loss will start to decrease again! This “double descent” of the loss gives a rationale for the use of staggeringly huge models that has become popular lately (GPT-3, SimCLR, etc.). See more about it in this blog post by OpenAI or the excellent post by Mike Clark.

Double descent in learning (from OpenAI's blog post)

-

Imitation learning: As its name suggests, imitation learning is a form of learning where an algorithm has access to an expert exhibiting the exact desired behavior that we want to reproduce. This is particularly used in a reinforcement learning context, in particular when the rewards are too sparse for an agent to retrieve a meaningful signal out of them. While imitation learning is still quite a niche among the huge corpus of ML research, it seems an important aspect of many forms of intelligence (and particularly PhD student intelligence: what would we be without postdocs and PIs that we can try to imitate?), and is one of the promising ways to solve challenges in complex and highly hierarchical environments. It was featured these last few years in the MineRL competition which aims at developing agents capable of mining a diamond in the video game Minecraft. Contrary to many other challenges solved by AI, this involves extremely sparse rewards, unattainable without careful planning conducted over hours of playing.

Agent playing Minecraft -

Lottery tickets: one of the most fascinating subjects of the last few years in the domain of ML, which I have already covered last year here. It shook the community in many ways, showing how small networks who happened to have the good initialization weights (Frankle and Carbin said they had “won the initialization lottery”) were able to match the performance of networks 10 times larger here, or even that pruning could replace gradient descent as a learning algorithm (!!!) here (see also “torch.manual seed(3407) is all you need” and watch deep learning researchers sweat). It kept leading to interesting developments and made its way closer to theoretical neuroscience, in particular through the work of Brett Larsen which linked it to dimensionality in the parameter space, showed the existence of a critical dimension above which training could succeed in a random subspace, and gave insights on how lottery tickets could be built. This all shows how little we know about learning in networks yet.

-

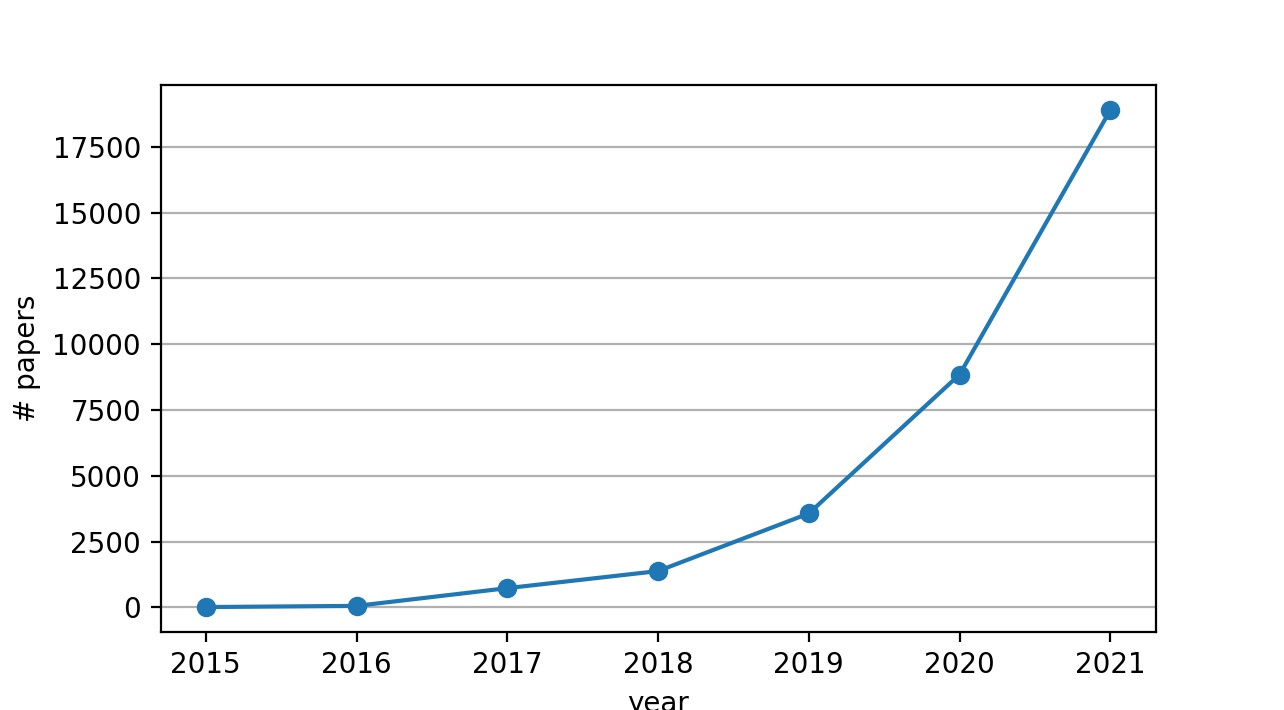

Self-supervised learning: This is really THE buzzword of the last few years, THE subject that exploded inside the community of machine learning, driven by the unbridled enthusiasm of many leading researchers like Yann LeCun who recently called it the dark matter of intelligence. You can see below in a small count of published papers I put together how its popularity exploded and quite reach its climax soon.

Now, what is this new frenzy about? Although hard to define exactly, self-supervised learning seems to consist in the application of supervised learning methods without any use of manually annotated data. That is, a self-supervised method must contain a way to generate labels from a raw dataset, and then train a supervised algorithm on that data. Given that it works on unlabelled data, self-supervised learning can technically be considered as a subset of unsupervised learning.

An archetypal example is found in the field of natural language processing, where both word embeddings (like word2vec, GLoVe) and general-purpose models like GPT-3 are trained by the following procedure: take a huge corpus of text, remove some words, and train a standard feedforward network to predict the most probable words for each gap. You will get a model which has a quite fine understanding of the relationships between words in written language, able among other things to generate text or perform question answering, and all that without any human intervention. Isn’t that wonderful?

I say a little more about the use of self-supervised learning in the realm of computer vision in the “contrastive learning” entry of this post. Contrastive learning is indeed one of the main approaches to these methods. Other applications exist, for example in the domain of video: one can train an algorithm on a dataset of videos simply by asking it to predict the next frame, or in time-series in general. It will then be able to generate similar data or create predictions “online”.

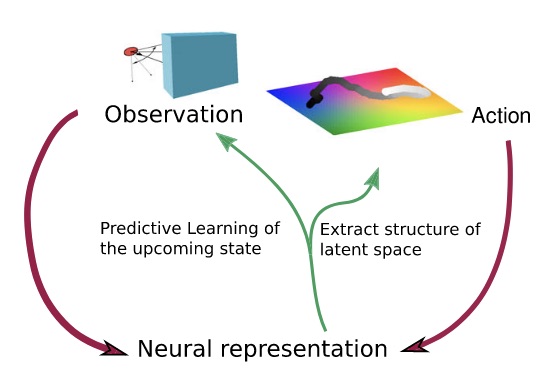

Now, if you are a pure neuroscientist, should this trend matter to you? I would say that self-supervised learning already made its way into neuroscience, for example through the work of Stefano Recanatesi in Nature Communications, who precisely trained a model to generate predictions about its future states as it was exploring an artificial environment. This is an exact application of self-supervised learning which reveals interesting latent representations in the obtained model, like some form of grid cell code. But most generally, self-supervised learning is by no means a stranger of the worlds of neuroscience of psychology, where it was known under different terms, like the extremely famous “predictive coding” framework, and probably many others which I don’t know about. It is interesting to see that this old, often theoretical, idea about brain function has become successful and practical among computer scientists, and could come back to neuroscience to shed light on biological intelligence, just as deep learning and RNNs did before.

Count of papers mentioning SSL per year (source Google Scholar)

Predictive learning concept (Recanatesi et al. 2021) -

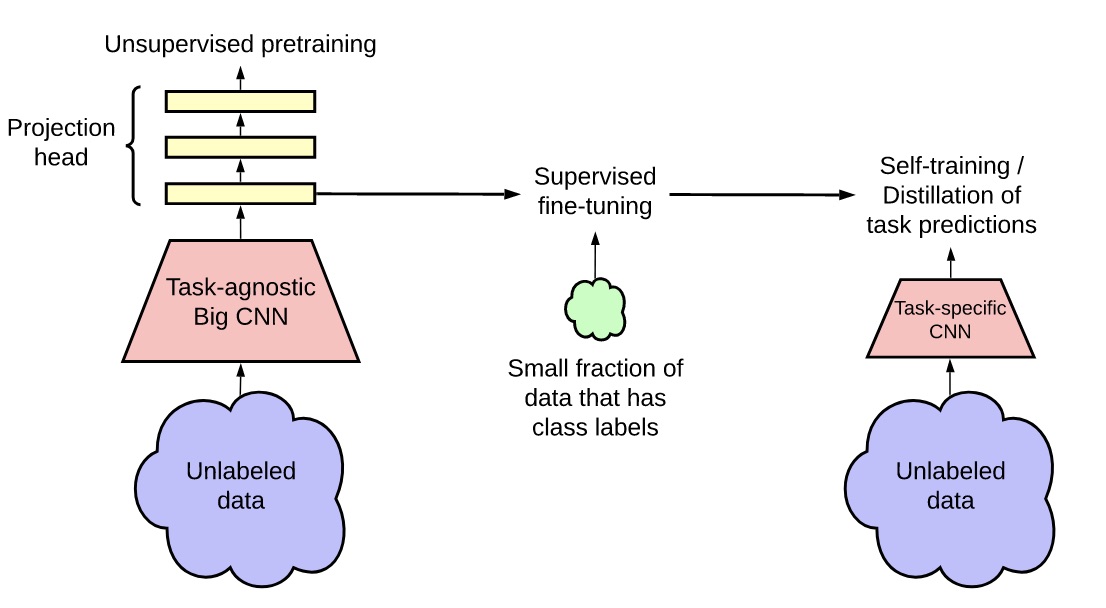

Semi-supervised learning: Paradigm that tries to make the best of a big dataset, of which only a small portion is labelled. This can occur in quite a lot of settings: for example, one could have access to a huge bank of images, but a limited amount of human workforce to label those and train a model. Another situation can be for automatic translation between languages for which a limited number of bilingual texts exist, but where we have large corpuses in each of the two languages. The methodology often goes by the motto unsupervised pre-train, supervised fine-tune which means that you would start by applying a self-supervised algorithm to the large corpus while ignoring the labels, and then fine-tune your model on the small labelled portion. Moreover, you can take the same pre-trained model and fine-tune it on different domains of expertise: for example a language model can then be applied both to generate word embeddings, perform question answering, or generate poetry. In computer vision as well this method applies very well, and all the better with overparametrized models, hence the title of the paper presenting the SimCLR2 algorithm, “Big self-supervised models are strong semi-supervised learners” (which only needs 1% of ImageNet to achieve a very good performance). Or in other words, these models have learned to learn quickly.

Semi-supervised pipeline, from the SimCLR2 paper (Chen et al. 2020)

Other things that didn’t make it here: research on the use manifolds in neuroscience and AI, use of topological methods like persistent homology (see this), progress in BCI with for example Frank Willett’s performance in decoding handwriting from motor cortex here, transformers for computer vision…